[My Recipes For Your Home]

When my grandmother gave me her superb edition of L’Art Culinaire Moderne, she also entrusted me with two much-loved little books, which had belonged to her mother before her.

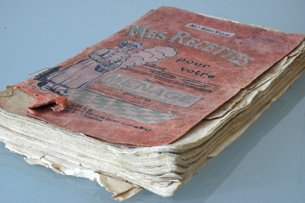

Mes Recettes Pour Votre Ménage and Mes Recettes Pour Votre Dessert (“My recipes for your home” and “My recipes for your dessert”) are two books in a series of three that were written during World War I, and republished several times after that — I have the 9th edition. The third book was called Mes Recettes Pour Votre Cuisine (“My recipes for your cooking”) but I have just two torn pages from that one — the asparagus section if you must know. My grandmother explained that the author was a popular columnist for La Croix du Nord, a catholic newspaper from the North of France. Under the nom de plume Marmiton (kitchen boy), he answered reader’s questions and shared tips and advice — sort of a Dear Abby for the homemaker.

Mes Recettes Pour Votre Ménage begins with a section on canning and preserving food, with recipes for syrups, liqueur and jams. (In passing, I was very surprised to see that one of them calls for agar-agar, to be purchased from your phamacist.) The second section is called Economie Ménagère (home economics), and holds an enchanting miscellany of tips to take proper care of your home and yourself. How to clean silk stockings and lace, how to revive rancid butter, how to prevent and cure chilblain (engelures in French), how to get rid of wasps, ants or toads, how to make purple ink (that’s a good one: mix red ink with blue ink), how to clean bird wings to decorate your hat, how to salvage a wet fur coat: life-saving advice for every ménagère.

The second book, Mes Recettes Pour Votre Dessert, is dedicated to “young women and especially fiancées, hoping that these humble pages offer a few secrets to create pure and soft happiness in their futur home”. It presents over 750 recipes for cakes, cookies and various desserts. Many are classic French recipes — génoise, moka, financier — but there are also quite a few forgotten or unusual ones, such as chocolate mayonnaise or um, potato madeleines. Most of them give precise measurements and would be very much usable today, but I had to smile at the recipe for babeluttes, a type of candy made with molasses, brown sugar and milk: it calls for 10 centimes (cents) of molasses, “at the pre-war price”. Very handy. There is also a recipe for sorbet à la neige (snow sorbet) in which you simply mix together jam and freshly fallen snow: no quantities given, but I have a feeling it shouldn’t be attempted with 21st-century Paris snow anyway.

Even the ads have a sweet, quaint charm to them: there is one that simply says, “Mangez du bon riz. Le riz Drapeaux est vraiment bon.” (Eat good rice. Drapeaux rice is really good.) Straightforward, efficient, and convincing: wouldn’t it be refreshing if modern-day advertisers tried to recapture that approach?

Those books are written in a warm, kind voice, and have definitely been put to intensive use — much more than any of mine will ever be I’m sure. Dog-eared and well-worn, they’re smeared with cake batter in places, decorated with kids’ doodles in others, and the pages are hanging on to a thread or simply missing. Though I have yet to cook anything from them (you’ll be the first to know when I do), I like to leaf through their fragile pages, picking tips and recipes at random for a fascinating trip through time.

The only problem is, whenever I handle them they sprinkle little specks of yellowed paper everywhere, and I’m anxious not to worsen the shape they’re in — my great-granddaughter would never forgive me.