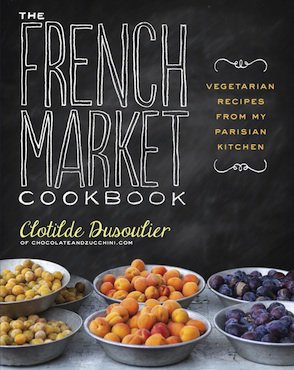

We have just wrapped up the final photo shoot for my new book about vegetables and French cuisine, and as someone who loves to know how things work behind the scenes, I thought I would tell you a bit about what the process has been like.

For my first two books, I shot all the pictures myself, but I felt that being a one-woman-band was not the most relaxed experience of all, so for this new project I wanted to work with a team of pros to produce the photos.

This meant finding a photographer and a stylist for the photos of the finished dishes, and I was hoping to work with Françoise Nicol and Virginie Michelin, because I loved what they had done for Alain Ducasse’s Nature book. They were up for it, and my editor approved the choice after looking at their portfolios, so we were in business.

Because produce and seasonality are central to my book, it was important to me that we shoot each chapter in season. Had we shot everything at once, as is often done for practical reasons, we would have had to work with out-of-season fruits and vegetables, and it would have bothered me (a lot) to practice the opposite of what I was advocating. A secondary bonus was a lower food budget, since seasonal produce is generally cheaper.

The one hiccup in this carefully laid plan was that the stylist injured her hand a week before the fall shoot, so we decided to postpone it until she had fully recovered, and shoot fall and winter back-to-back. This was doable without compromise because, in truth, fall market stalls are not that different from winter ones, and it turned out to have a silver lining: instead of enduring the dark of December, we were able to benefit from the longer, brighter days of late February.

There are a hundred recipes in the book, but I had a budget for forty-eight food photos (plus an additional twenty-eight ambiance and market shots by Emilie Guelpa), so in preparation for each seasonal shoot, I had to select which dishes would be photographed. I chose the ones I thought would be most interesting to look at, and also the recipes I felt would benefit from a visual illustration, if they involved a particular dough-folding technique for instance. I then considered the selection as a whole, and made sure it was well-rounded and balanced in terms of dish type, color, etc.

The next step was to translate the recipes from English to French and send them to the stylist a couple of weeks before the shoot, so we could discuss the mood and presentation of each dish, and she could start gathering the necessary props and ingredients.

For each shoot — spring, summer, then fall/winter — we convened at the stylist’s house, and set things up for the next few days: depending on the complexity of the recipes, and how many hours of daylight we had that time of year, we were able to shoot four to six dishes a day.

The stylist, who was in charge of preparing the food (with a bit of kitchen help from me, and from an assistant for the final shoot), would get things started for a particular recipe. And while the various elements were marinating or resting or simmering or baking, we discussed props: what background to use (among a selection of fabrics, wooden planks, painted boards, stone slabs…), what dish or dishes to place the food in, and what accessories (glasses, silverware, napkins…) to add to bring additional life to the scene. Once we had those down, we tried to find our ideal composition for the shot and the best angle from which to shoot it.

The challenge was to instill a common style throughout all the photos, but make sure that each season had its own mood, and that each shot was distinctive: we paid close attention to color schemes, props we may have used in previous photos (though I’m not opposed to the occasional resurfacing of a dish or accessory, as long as it plays its role a bit differently), and types of backgrounds, again, to ensure a well-rounded and balanced look.

We would then move on to the more delicate and time-sensitive step of plating the food, and showing it at its most appetizing, fresh, and alive for the camera to capture. Small tweaks would be done at that point — adding a touch more caramel sauce, rotating the almond that’s catching too much light, adjusting the position of the salad leaf that’s pointing up awkwardly — and sometimes we would try a couple of different options to choose from later.

My mantra throughout those days was “la vraie vie” (real life), so much so that the stylist and photographer quickly started teasing me about it, but it was important to me that the shots reflect a credible, realistic scene.

Of course, to produce a pleasing image, you do have to use the occasional trick to work around the laws of perspective, prop things up, or add a bit more shine to those herbs. And of course, viewers understand that a food photo is like a miniature theatre set: it’s pretend. But I prefer my food presented simply, and I didn’t want any fuss or artifice that would make for a pretty image but wouldn’t be consistent with a real-life situation, such as ribbons tied around muffins, or raw ingredients used in the recipe scattered on the table (who does that?).

And I would always try to imagine the story we were telling. Not elaborate stories with a plot and tension and resolution, but just this: are we looking at the food just as it’s been brought to the table? Has someone just cut out a serving and put it on a plate? Is this the plate of someone who’s just started eating? Can we tell if that food is meant to be shared, or if it’s a single person’s serving, and if so, is the amount of food about right?

These basic principles — and the stylist’s and photographer’s talents, naturally — have allowed us to produce what I think is a lovely collection of shots that I hope will catch the reader’s eye, whet his appetite, and make him want to rush into the kitchen and cook. I very much wish I could share them with you in advance of the book’s publication next year — the wait is killing me! — but I hope this gives you an idea of the work involved in creating them.

Have you ever attended, or taken part in, a photo shoot? Were things done differently? And if you have questions about the process, feel free to ask in the comments, I’ll do my best to answer them!