This is part of a series on French idiomatic expressions that relate to food. Browse the list of idioms featured so far.

This week’s idiom is, “Être comme un coq en pâte.”

Literally translated as, “Being like a rooster in dough,” it means feeling cosy and pampered, being in a state of absolute contentment, with one’s every need catered to. I’ve seen it likened to the English idiom, “being in clover” or “like pigs in clover,” but I understand the latter refer primarily to financial comfort, whereas the French expression implies a more general sense of physical and spiritual well-being.

Example: “Quand il est chez sa grand-mère, il est comme un coq en pâte.” “When he’s at his grandmother’s, he’s like a rooster in dough.”

Listen to the idiom and example read aloud:

(If no player appears, here’s a link to the audio file.)

Coq en pâte (literally, rooster in dough) is an olden, luxurious French dish in which a poularde (fatted chicken*) is stuffed, trussed, wrapped entirely in a short crust, and then baked until golden. It is traditionally served with sauce Périgueux on the side, a sauce flavored with port and truffles.

The idea behind this seventeenth-century idiom is that the bird, while it is being prepared for this recipe — handled with loving care, adorned with prized ingredients, and bundled up snugly in a buttery blanket — must feel really, really good. (One might argue that its bliss is short-lived, but this idiom is perhaps a good illustration of how the French popular wisdom considers it an honorable thing for an animal to finish its life as a delicious dish on a plate.)

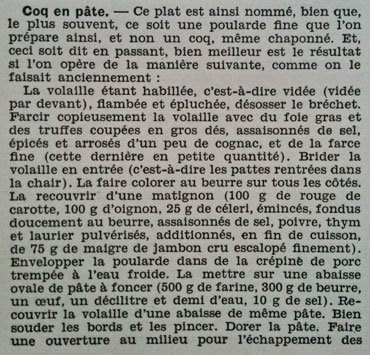

If you’re curious, or maybe in need of inspiration for your Christmas menu, here is the recipe for Coq en pâte, as found in my grandmother’s 1938 Larousse Gastronomique — the very twin of the one Paul Child gives Julia for her birthday in the movie (abridged translation follows):

I’ll note that the recipe also appears in the most recent edition of the Larousse Gastronomique (just published in English), but the typeface and wording are less charming.

[Quick-and-dirty translation: start with a ready-to-roast fatted chicken, with the wishbone removed. Make a stuffing with thickly diced foie gras and truffles, seasoned with salt, spices, and a little Cognac, and combined with a small amount of farce fine [Clotilde notes: that’s a poultry stuffing made of veal, pork, poultry liver, and breadcrumbs].

Truss the chicken with its legs folded back tightly into the flesh. Sear in butter on all sides to color. Coat with a matignon (100 grams carrots, 100 grams onion, and 25 grams celery, finely minced, cooked in butter until soft, seasoned with salt, pepper, ground thyme and laurel, and combined with 75 grams finely chopped cured ham). Soak a piece of pork caul in cold water and wrap the bird in it.

Make a dough with 500 grams flour, 300 grams butter, an egg, 1.5 centiliters water and 10 grams salt. Spread the dough out into an oval, and place the bird on it. Make a second, similar dough and cover the bird with it. Bring the edges of the top and bottom doughs together and pinch to seal. Brush with eggwash. Create an opening in the middle so the steam can escape. Bake in a hot oven for about an hour.

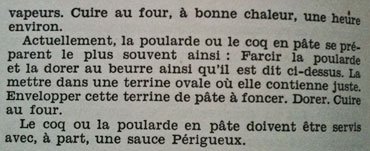

These days the dish is often prepared this way: stuffed and sear the bird as above, place it in a terrine dish large enough to accommodate it, and covered with dough across the top. Brush with eggwash and cook in the oven.

Coq en pâte is to be served with a sauce Périgueux on the side.]

* The term coq (rooster) is sometimes used in culinary French where it is in fact preferable to use a poularde (fatted chicken) or a chapon (capon), if available. Because the rooster is kept around for reproduction purposes, it is old when eventually slaughtered, so it isn’t the choicest type of poultry.