Did you know that France produces more than 350 types of cheese? Each variety is the unique result of a specific production method and aging process, requiring both technical skill and intuition.

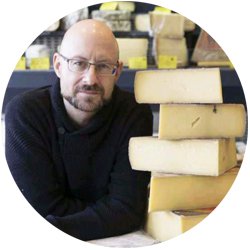

We talk about cheese a lot on Chocolate & Zucchini: we’ve covered how to shop for cheese and the notion of cheese terroir, and today I am happy to present a guest post by Jonathan Deitch, a.k.a. Monsieur Fromage, a fellow bilingual blogger and passionate explorer of all things cheese.

We talk about cheese a lot on Chocolate & Zucchini: we’ve covered how to shop for cheese and the notion of cheese terroir, and today I am happy to present a guest post by Jonathan Deitch, a.k.a. Monsieur Fromage, a fellow bilingual blogger and passionate explorer of all things cheese.

Jonathan is an American who’s lived in France since 2009. He recently attended an intensive two-week professional workshop at Académie Opus Caseus, the cheese industry’s center for education. He has generously offered to walk us through the process of making and aging cheese, with lots of quirky details for us cheese geeks to lap up.

Please visit the M. Fromage blog, and follow him on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you Jonathan!

Part Magic, Part Biochemistry

Goat cheeses sampled on Cheese Day in Paris, in January 2016. Note the blueing on the rind.

My recent two-week professional training with the Académie Opus Caseus was an eye-opening introduction to affinage, the process of aging cheese. The principles and techniques are simple to understand, yet they take a lifetime to master. They also serve as a good reminder of the importance of environment and tradition, and the value of patience, honest labor, and passion.

To understand the aging process, we need to start with how cheese is made, and wrap our minds around the fact that the best cheeses are a direct result of flora, a less-scary term for the (good) bacteria, yeasts, and molds that contribute to taste, texture, smell, and appearance.

Connecting Flora to Flavor

Cheese is made from milk. Milk comes from animals, such as cows and sheep and goats. Animals eat grass and flowers and hay. Whether we imagine a bucolic pasture or a giant industrial milk operation, this setting is an entire ecosystem of flora that will play a major role in the cheese making. Cheese is a living product because it comes from living things.

Cheese making starts off the same way for virtually all cheeses. Milk is heated to at least the body temperature of the animal, and naturally occurring bacteria will cause the milk to “sour” and become acidic. Stop here and you have yogurt.

Let’s keep going and add rennet, an enzyme that causes casein, the essential protein in milk, to coagulate. The water separates as the milk solids (i.e. protein, milk fat, and lactose sugar) clump together. These clumps are called curds and they look a bit like panna cotta floating in a yellowish liquid called whey.

Rennet causes the milk solids to curdle and separate from the liquid whey.

At this point, if we simply shape the curds and drain out the whey, without aging, we have fresh cheese. Good, but not as good as it can be: though still undeveloped at this stage, the cheese already contains almost all the flora it will need for taste, texture and smell. It is the affinage that will completely transform the curds.

The curds are placed in molds which will be pressed and dried.

Rind Development

The rind (or crust) of cheese begins to form during the initial drying process. What happens next depends on the type of cheese; many are washed in a dilute salt solution, or a solution with alcohol or bacteria cultures:

- Soft blooming-rind cheeses, like Brie and Camembert, are salted and washed with a solution containing penicillium molds, which creates the white rind.

- Soft washed-rind cheeses like Munster, Pont L’Évêque, and Langres are washed with dilute solutions containing salt and/or alcohol.

- Hard cheeses, like the French Basque Ossau-Iraty, are washed with a dilute solution of salt and bacteria, or morge in French.

Liquids and morges are added early on in the cycle. Later, the cheeses will be brushed or patted to spread the flora over the crust, flipped regularly, carefully observed, and tasted to gauge the progress.

Rind development on my hands from patting mucor mold on the rinds of 80 Saint-Nectaires.

Rind development serves several purposes. Not only does it add aroma and flavor from the outside, it creates the conditions for flora activity inside the cheese as well. Finally, the growth of desirable flora on the rind creates competition that prevents the appearance of undesirable flora.

Paste Development

Paste (pâte in French) designates the inside of the cheese, where bacteria are busy breaking down the raw materials of milk — proteins, fats, sugars. Complex biochemical reactions are at work and we can see, taste, touch, and smell the transformation.

For example, if you see holes in the paste of the cheese, that’s evidence of proteins breaking down. A camembert or brie will go gooey just under the crust as the fats break down, and it’s the sugar breakdown that creates acidic flavors in goat and soft cheeses.

Caves and Environment

The affinage environment plays a central role in the development of the cheese. The affinage room is called une cave in French, or cellar. This can be a simple room (not necessarily below ground), a natural cave, an abandoned railway tunnel, or even a trailer. What matters is that the affineur, or cheese ager, be able to regulate humidity, temperature, and air movement, in order to stimulate or retard bacteria and mold growth.

For example, Roquefort are “put to sleep” for months: they are kept at a very low temperature (2-4°C or 36-39°F), to make this blue cheese available to consumers year-round, regardless of the sheeps’ natural lactation cycle. The mold would grow too quickly otherwise.

Standardized Versus Consistent

While the essential process of cheese aging is scientific, it is hardly regular, and depends greatly on the animals’ diet, the season, the weather… The slightest variation can create a butterfly effect. Some of this variability we seek, as it contributes to taste. But variability can spell trouble, sometimes leading to waste or spoilage.

It is up to the cheesemaker to decide how much variability she or he wants to deal with, and there are two approaches. One is to standardize by eliminating sources of risk, and this is what industrial producers do. Through intensive farming techniques (controlled diets, highly regulated living and milking conditions, milk pasteurization, and machine driven aging), they reduce variability and increase the scale of production.

The primary downside is that standardized cheeses are boring, with as much gastronomic depth as Playdoh. Americans will know what I mean from the insipid Bries available state-side; French readers can just imagine a President-brand camembert.

The alternative approach is to embrace the ecosystems (of the farm, the cheese making room, the affinage cave) and focus on consistent practices. The more consistent the practices, the more consistent the cheeses will be. Process control and a disciplined approach are key to tracing changes and understand their causes.

The human relationship between farmer and maker, and between maker and affineur, are just as capital. In turn, the affineur will work with the distributors and retailers to ensure the cheeses are properly handled and stored. This fluid system does yield more variability, but also cheeses richer in flavor, smell, and texture.

Just an ordinary day in Auvergne, the region known for Cantal, Fourme d’Ambert, and Saint-Nectaire.

Raw Versus Pasteurized

Whether industrialized or artisanal, cheese making is all about bacteria, and everyone from the farmer to the retailer shares the responsability for food safety. They reduce the risk through exacting hygiene practices, regular testing of the milk and the environment, and traceability, which tracks cheeses precisely from one actor to the other.

Opinions differ on milk treatment. A country like France, where there is a long and cherished tradition of making cheeses with raw milk, represents one end of the spectrum. A country like Australia, where cheeses must be made from pasteurized milk, is at the other. The United States is somewhere in between.

Raw milk cheeses are gastronomically superior, and scientific studies have shown they are safe to eat*. They are starting to make a comeback in the United States, thanks in part to organizations like the Oldways Cheese Coalition and the American Cheese Society who have partnered with the Food and Drug Administration.

France is a little bit of a paradox. Despite being a cheese-rich and cheese-loving country, the majority of cheeses consumed are industrially-produced and pasteurized (gah!). Giant agribusiness producers continue to chip away at, and food activists continue to fight for, the system that preserves tradition: the AOC/AOP program.

AOC stands for appellation d’origine contrôlée (appellation of controlled origin) and sets strict requirements on the cheese making and affinage process, and the geographic origin of the cheese. You can’t call a cheese Camembert de Normandie or Comté unless it’s been made in the designated region and in a specific way. These appellations are awarded not just to cheese, but also wines, butters, meats, fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, and oils. The program has been expanded across the EU, where it’s known as AOP or appellation d’origine protégée; in English, PDO or Protected Designation of Origin.

“Flights” of cheese at different stages of ripeness. Row A is Camembert de Normandie; row B is a goat cheese from Provence; row C is Langres, a washed rind cheese from Champagne. Can you guess which is youngest/oldest in each row?

Cheese Tasting

You and I could geek out on the science of affinage for hours, but the proof is in the pudding. As part of our training, we learned about sensorial analysis, which involves more than just the tasting.

Visually examining the rind and shape of the cheese tells you a lot about external and internal flora, how humid or dry the cheese might be, and what techniques were used in making it.

By smelling the rind and paste, you pick up scents of fruit and herbs, nuts and butter, toast and caramel, sweet or sour milk, or the alcoholic smell some cheeses give off.

Finally, taste brings an indication of salty, sweet, sour, and bitter, but also the lovely meaty or mushroomy umami that characterizes a ripe Brie. This creates what the pros call trigeminal (try-gem-uh-nal) effects on the sides of the mouth and jaw, which can be experienced as piquant sensations or the taste of minerals.

The experienced taster immediately picks up on a cheese that has gone over to “the dark side,” as Laurent Mons and Sue Sturman from Academie Opus Caseus like to say. An overly aged goat cheese becomes hard and tastes soapy, incorrectly tended bries and Munsters can get ammoniated, and if a chemical reaction takes a bad turn, it creates the smell of baby sick (sorry!).

Try doing a tasting of cheeses from the same families; here, a plate of three pressed cooked cheeses along with three blue cheeses.

Tips on Buying Good Cheese

Clotilde has shared cheese-buying advice with you; let me add my top tips:

Ask questions. People who love cheese love talking about it! You’ll find out a lot about the cheeses and the cheese monger’s perspective by being curious. Here are two questions I like to ask to get the conversation going:

- I got <insert cheese> last time I was here. Do you have anything similar?

- Can you recommend something that is a little out of the ordinary, or that I might not have heard of?

Smell and taste your cheese. Ask your cheese monger for a sample; don’t be intimidated! Put it up to your nose and smell it before you taste it.

Build up your own database. The more cheeses you eat, the more you’ll learn, so try to gradually broaden your horizons and keep notes. Try different cheeses of the same type or technique, or the same region. If you have access to enough variety, you can do “flights” of cheese, tasting the same cheese at different ages, to see how the cheese develops with the affinage. In France, it’s fairly easy to do this with Comté, as cheese shops typically offer it at different stages of ripeness.

Now Get Out There and Eat Some Cheese!

I hope this has given you some pointers on cheese aging, and that it encourages you to try artisanal cheeses of any origin. My focus has been on French ones because it’s where I live and study cheese, but there are terrific cheeses to be found all over Europe, in the UK, and the US.

Please share your favorites in the comments below, we’d love to hear about them!

Don’t miss:

• 6 Tips to Buy Cheese Like The French

• Terroir Products: What to Eat in the Jura

• How to taste chocolate

~~~

* In France, the official recommendation for pregnant women is to avoid soft blooming and washed rind cheeses, especially those made with raw milk, and to remove the rind on all cheeses. This is meant to reduce the risk of listeria infection. Hard-pressed cheeses are fine, including those made with raw milk, since the milk is sufficiently heated in the process.