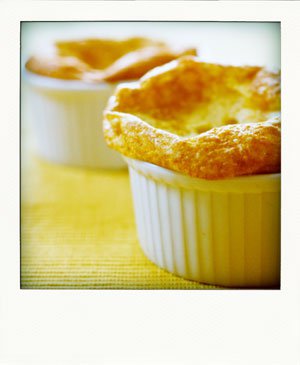

I grew up in a household where le goûter is a cardinal ritual, and I can safely state that I’ve been eating an afternoon snack practically every day for the past thirty years.

It is so much a part of my food habits that I actually size my lunches to make sure I’ll feel a bit hungry around 5 or 6, and in need of something — say, a blueberry oat bran muffin — to tide me over until dinner. It is also a welcome alibi to look up from whatever it is I’m working on, make myself a cup of tea (or, these days, iced coffee), sit by the open window, and relax.

Oftentimes, it’ll just be a piece of fruit, and my go-to afternoon treat is an apple, chilled and sliced. But I buy my apples from an organic grower located in the Val de Loire, and that leaves me high and dry from June, when he sells the very last of his somewhat shrivelled but super sweet storage apples, until September, when he brings in the shiny, crisp new crop.

Cue these blueberry oat bran muffins, which, despite their good-for-you bran content, don’t taste like a punishment devised by some misguided flower-child baker.

(The one exception to this rule is a wonder of nature I’ve only discovered this summer, called pommes de moisson (“harvest apples”), picked from trees that bear fruit briefly in August. This coincides with the traditional harvesting season for wheat in France, hence the name. My mother first bought pale green ones for me at the Gerardmer greenmarket earlier this month, and a week later I found larger, bright red ones at the Batignolles farmers market. Ever heard of anything similar?)

So then, from time to time, and more so during the apple-less months, I have to have cake, or some sort of baked good, for such is the spirit of le goûter: something homemade and unfussy, not overly sweet, and not too much of a nutritional black hole.

Cue these blueberry oat bran muffins, which hit all four bases and, despite their good-for-you bran content, don’t taste like a punishment devised by some misguided flower-child baker. (But then I really like oat bran.)

I should note — and this is a curse inflicted upon all muffins, sorry Tim — that these taste best on the day they’re made, when the tops still bear their delicately crusty crown. But the flavor is still lovely on subsequent days, and if you wish to revive the memory of the fresh-from-the-oven texture, you can always pop the blueberry oat bran muffins upside down over the toaster (I have a little rack for just that purpose), or for a minute or two in the toaster oven.