I have a special bookshelf where I keep the books I plan to read. Some of them I’ve bought myself, and some of them I’ve borrowed, mostly from my mother or from my neighbor Patricia. At latest count — let me get up from the couch and count them for you — there are thirty-two books there. As you will infer, I am a bit of an unread-book hoarder, and I don’t feel quite serene unless this stash is well fed.

Perhaps my most cherished moment in the whole reading experience is when I kneel in front of the shelf (it is a low shelf), twist my neck this way and that to read the titles (English books have you bend your head to the right, French books have you bend it to the left, and my shelf is not very well organized), check my reader’s pulse to know what I feel like reading now, pull the chosen book by the spine (the others, while disappointed, let out a little sigh of relief — they have a bit more room to breathe now), and relocate my bookmark (a very old tattered thing) from the previous book to the promising new one.

Some of the books on my shelf have nothing to do with food — a couple of Simenon novels, Zadie Smith’s latest, a biography written by Jonathan Coe, a series of short novels about the Inuit people, an essay about Paris’ street life in the 18th century, my father’s two latest Le Guin translations — and some do — Hemingway’s Moveable Feast, a book on chocolate, Jeffrey Steingarten’s second collection of essays, and a history of French cakes and pastries, a fascinating thing into which I’ve peeked already, in a patent breach of my official rule.

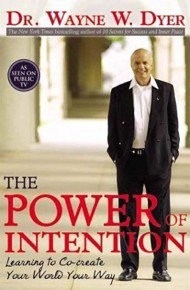

Some books find themselves waiting for months in this temporary settlement — fortunately, my two favorite book lenders don’t seem to mind — but some barely have time to unpack their stuff. The most recent example was Laurie Colwin’s first collection of essays on food, called Home Cooking: A Writer in the Kitchen.