Once you have a natural starter alive and kicking on your counter, stealing the occasional banana from the fruit bowl, it’s hard to go back to baking bread with commercial yeast.

Not only would that feel like a bit of a betrayal (though you can always blindfold the jar of starter or work under the cover of night) but every loaf is an opportunity to strengthen your starter as well as your skills. And frankly, you’ve gotten used to the vivid flavor and lasting freshness of sourdough-powered bread, so you’re a bit spoiled.

Most breads leavened with commercial yeast can be leavened with a natural starter. It is just a matter of converting the recipe; all you need is a calculator and a play-it-by-ear disposition.

That’s not to say you want to limit yourself to those recipes written with a starter in mind: even though baking with a natural starter has the ancestral high ground and is regaining considerable popularity of late, it is still practiced by a minority of home bakers, and most of the bread recipes out there call for commercial yeast.

But of course, most breads (see caveats below) leavened with commercial yeast can be leavened with a natural starter. It is just a matter of converting the recipe; all you need is a calculator and a play-it-by-ear disposition.

So, how do you go about it? There is no single method* but I have had good success with mine, so I wanted to share it with you below. If you want to chime in with your own method and experience, I’ll be most interested to hear them.

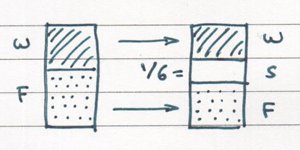

My approach is based on my love affair with Flo’s 1.2.3 formula, in which the bread dough is made by combining 1 measure of 100% starter (= a starter that’s fed an equal weight of flour and water at every meal), 2 measures of water, and 3 measures of flour — all measures understood in weight. This means that the bread dough ends up being made of 1⁄6 starter (and 2⁄6 water and 3⁄6 flour).

Example: I make my standard loaf with 200 grams 100% starter, 400 grams water, and 600 grams flour. Once all these ingredients are combined, my bread dough weighs 1,200 grams, or 1.2 kilos (I’m neglecting the weight of the salt), 1⁄6 of which is the weight of the starter [1,200 ÷ 6 = 200].

A natural starter works its magic at a much slower pace than commercial yeast, so I’ll allow for a longer resting time than stated in the yeast-based recipe.

When I want to convert a recipe that uses commercial yeast, I aim for that same starter ratio: I add up the total weight of water (and any other liquids) and flour (or flours) in the dough, and estimate that I’ll need 1⁄6 of that weight in 100% starter to leaven that amount of dough. (Any ingredient that is neither liquid nor flour, such as nuts or seeds or fat or sugar, is neglected here.)

Example: Let’s say I want to convert a yeast bread recipe that calls for 415 grams water and 605 grams mixed flours. The total water + flour weight is 1,020 grams [= 415 + 605], and I estimate I’ll need to use 1⁄6 of this weight in starter, which amounts to 170 grams [= 1020 ÷ 6]. (I round the amount up where necessary.)

Naturally, because starter is made of flour and water (with a friendly colony of yeasts and bacteria), I can’t just add it to the rest of the ingredients and proceed without changing anything else; it would throw off the balance of ingredients, and therefore the texture. Instead, I need to account for the fact that my 100% starter is half flour half water by lowering the amount of water and flour accordingly.

Example: In the yeast bread recipe described above, I’m planning to use 170 grams of 100% starter, which is equivalent to half water and half flour, that is to say [170 ÷ 2 =] 85 grams of water and 85 grams flour. So I’m going to lower the amount of water and flour by 85 grams each. I will therefore make my dough by combining 170 grams starter, 330 grams water [= 415 – 85], and 520 grams flour [= 605 – 85], which all adds up to 1,020 grams bread dough [= 170 + 330 + 520], as originally intended.

Then, when the bread dough is mixed and kneaded, I’ll follow the rest of the recipe with a few necessary changes: a natural starter works its magic at a much slower pace than commercial yeast — thereby fostering the development of desirable flavor components — so I’ll allow for a longer resting time than stated in the yeast-based recipe. Sourdough-leavened doughs also ferment during a single rise (with absolutely no punching down), so the method may have to be modified in that regard as well. Key here is the use of one’s experience and observation skills to determine what the dough needs for this particular recipe.

Such conversions work best for “real” bread recipes, those that are chiefly based on flour, water, and yeast.

I will note that such conversions work best for “real” bread recipes, those that are chiefly based on flour, water, and yeast. If a dough is enriched by the addition of sugar, fat, or eggs, these elements tend to slow down or even inhibit the action of the starter, and the dough may take a very long time to rise, and might not reach its full potential. In such cases, I will use some of my starter as described below, but keep a portion (say half or a quarter) of the commercial yeast that the original recipe calls for.

All this is to say that, before you start converting and toying around with recipes, I recommend you take the time to get perfectly comfortable with your starter, the way it behaves, the feel of the dough, and the techniques involved. Once you’ve honed your skills on basic starter bread recipes, you’ll have developed enough of a baker’s intuition to successfully convert recipes.

* You can also take a look at the methods offered here, here, and here.