Have you read anything by Laurie Colwin?

She was an American author based in New York City, who wrote novels and also penned a column in Gourmet magazine for a few years, writing about her kitchen life in such a warm, witty, and approachable way that it was impossible then, and remains impossible now, for the reader not to develop a strong connection to her. These essays were published as two collections, Home Cooking: A Writer In The Kitchen and later More Home Cooking: A Writer Returns To The Kitchen, which have become cult reads for admirers of quality food writing, sharing shelf space with the work of M.F.K. Fisher, Edna Lewis or Alice B. Toklas.

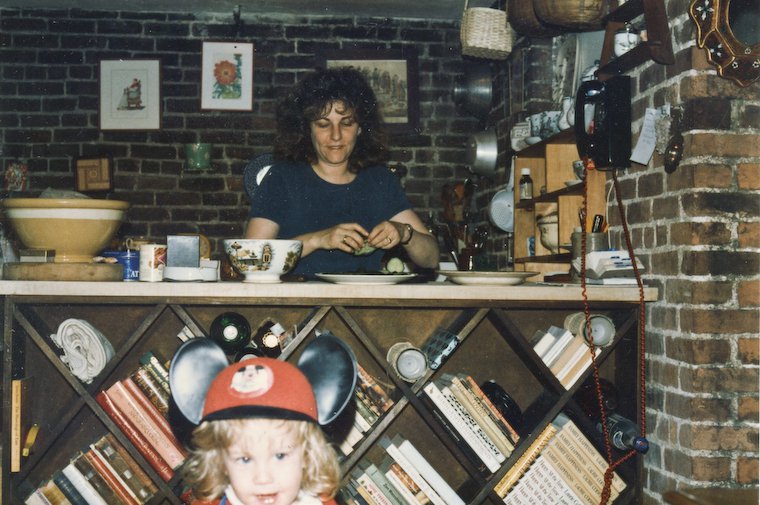

Ms. Colwin died unexpectedly in 1992, at the unfair age of 48, and left a child, RF, who was only eight at the time. RF Jurjevics is now thirty and works as a writer, animator, and multimedia producer — founding Big Creature Media a couple of years ago — and I had the opportunity to get in touch last fall, when Open Road released Colwin’s books as ebooks for the very first time, and offered the contact to promote this release.

I immediately jumped at the chance to feature Laurie Colwin, whose writing — both fiction and nonfiction — I greatly admire, as part of my Parents Who Cook series, in which I explore how children shape and inform a cook’s kitchen life. This is the first installment in which it is the child who speaks, and I am grateful to RF for sharing such touching and uplifting childhood memories. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

Please consider downloading one of Laurie Colwin’s wonderful books from Open Media, and do share any of your own memories or tips about cooking with and for children!

I was a headstrong kid and spoke my mind – asked or not. A teacher once wrote on a school report that I was the tallest in my class and that my mother had referred to me as her “Viking child.” I’m not sure if this was a nod to my Baltic heritage (though Latvians were not Vikings, to my knowledge) or simply to suggest that I was a bit brutish in manner and stature. I admit to being both of these things as a child!

My mother was a similarly opinionated person, and she seemed to like having an opinionated kid – even when we clashed over, say, what was and was not appropriate for my school lunch. Open dialogue was encouraged, but I was a handful (to say the least), and there were definitely many times that I wore my poor mother out with pestering, arguing, or throwing fits.

I adored my mother’s cooking. It would have been hard not to. She put so much care into it, so much thought, and really loved to do it. People flocked to her table, and were so happy to hang out in the kitchen as she cooked. She would constantly ask her dinner guests to taste things and give their honest opinions of them. She wasn’t a showy cook, or one who kept her methods to herself, but instead really delighted in sharing food, recipes, and conversation.

Still, there were times when it was hard to be the kid who ate the “weird food.” My mother had very strong opinions about things that were good and bad for kids and for people in general. Keeping perishables in plastic was bad. Making jam from scratch was good. She didn’t like to budge much on the subject of good and bad. Though a lot of my classmates and neighborhood chums learned that they loved gingerbread and salmon and asparagus at my house, I envied them their Oreos and American cheese slices and radioactively colored “juices” nonetheless.

There were times I wished that I could just be “normal” and get chocolate-laden granola bars in my lunchbox (a pink, formerly Barbie-themed plastic trunk with the doll decal scraped off and cat stickers in its place) instead of a kiwi fruit, or have Wonderbread on my sandwich instead of slices from a Bread Alone boule. Some battles I won (fruit roll-ups, the kind that involved peeling Little Mermaid characters from their centers) and others I lost (no store-bought cookies!), and so I continued to be the first-grader with the goat’s milk yogurt and smoked Gouda. Years later, an old friend told me how jealous she’d been of my lunch. “All I got was tuna fish,” she told me. “And maybe a yogurt. Your food was exciting!” And she was right.

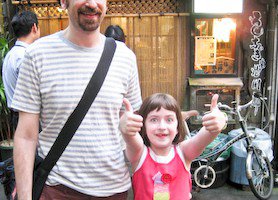

Laurie Colwin and then 2-year-old RF in 1986.

What did family meals look like when you were a young child (the good, the bad and the ugly)?

The meal I remember best was our standing Friday night roast chicken dinner. This was my mother’s version of a secular Shabbat. No prayers, but long, tapered candles and conversation – about our days, what we were looking forward to over the weekend, or what I learned at school. Her roast chicken was just heavenly, dusted with paprika, then slow-cooked (and basted!) in a pan for hours. I remember her carving it at the table and how juicy the meat was. Just perfect!

I also recall her dinner parties, too, how she’d put out the filigreed silver if we were having fish or a tureen if we were having soup. I got to pick the tablecloth, which was usually an elaborate sheet meant for bedding but also happened to fit our farmhouse table for ten quite nicely. The dinner parties would stretch long into the night, and I’d be put to bed before they were over. My room was next to the dining room and was closed off by two slatted doors, so I would fall asleep to the gentle sound of the guests’ voices and laughter.

The only ugly I can remember was the one time she tried to make fish head soup. She realized her mistake, though, and none of us had to eat it!

Do you think having a child changed the way your mother cooked, and if so, how?

After I came along, I think my mother really got to fuss in a way she never had before – and I say that with love, and as a positive thing! Fussing over someone doesn’t just mean restricting their intake of commercially made peanut butter, for example, but also means that the fusser may cut up the fussee’s toast into “postage stamps” when they are sick (a family tradition).

My mother got to watch me eat all these delicious things for the first time, and gauge my reaction to what she had me try. I was over the moon for salmon, apparently, and lemons. Cornichon pickles disappeared if left in my line of sight for too long, and I went nuts for rhubarb (just as my father did and does). I ate meat, fish, bread, jam, Indian food, Chinese food, Ethiopian food, black bean soup, and that goat’s milk yogurt. My mother loved witnessing my ‘aha’ food moments, and said in one of the cookbooks (I can’t remember which) that she wished she could go back in time and discover certain foods all over again.

My mother also made friends with my friends and their parents via cooking, and often had my classmates and their parents over for dinner, some of whom loved to share their own culinary favorites. One mother of a friend of mine had grown up in Hong Kong, so we all spent many hours in Chinatown together, gobbling up dim sum and poking around in the shops there. I still love the smell of those stores that sell dried roots, leaves, and even animals for medicinal purposes. Tourists turn up their noses and walk out (I’ve seen it happen), but I go right for the most pungent isle. It reminds me of those good old days.

Did your mother find ways to involve you in her cooking process, and if so, how? Do you think this came naturally to her, or did she make a conscious effort to include you in that part of her life?

I was in the kitchen with her all the time. My mother and I spent a lot of time together, as she worked from home and she had to get me from school in the afternoon. I’d either watch her prepare food or get right in the thick of it. She taught me to knead bread, roll dough, cream cold butter with sugar, and blend wet and dry ingredients. If I got too squirrely or underfoot, she’d set me up with a miniature of her favorite bowl and a tiny bit of whatever she was making. I was then free to mess about as I pleased and not get in her way.

When I got a bit older, I was more helpful. I made the salad dressing, for instance, which had been my mother’s childhood job, and set the table. I buttered pans, got all the gingerbread batter out of the bowl with a spatula, and folded napkins. Truthfully, I liked all the cooking and baking tasks better than the rest!

What are some of your fondest food-related memories growing up around your mother?

Oh, so many! One is from the year we made a black cake for Christmas. That thing has to age for while, so we baked it weeks in advance, storing it in a tin in the pantry. My mother wanted to make royal icing, a process I don’t remember, but I watched, fascinated, as she put it together. We also handcrafted marzipan decorations to top it off, and I recall being very proud of our work when it was all done and on the table!

I will also never forget how my mother positioned herself when she was cooking. She was prone to wearing these oversized sweaters, ones with thick stitching, and so when she was mixing or chopping or kneading, she pushed the sleeves all the way up past her elbows. She was not a tall woman, standing at just five feet, one inch, and so she had to make the most of her force when she was dealing with stubborn dough or a dull knife or a big roast, and also worked without fancy gadgetry. No electric mixers, pulverizers, or anything of the sort for her! We had a blender, though, and a hand-crank eggbeater, and a hand-held mixer that my dad and I used to make egg whites for his famous pancakes. I don’t think my mother ever touched it, though. So she was pretty physical in the kitchen, mixing things in big bowls or chopping up vegetables for stews.

What would you say are the most important lessons you learned from her about cooking and eating?

Hmm. Well, I did learn to make a mean gingerbread, and have inherited her gadget-free method. I think the biggest thing I took away from our life together, though, was how unifying food can be. No matter who we are or where we’re from or where we’ve been or where we’re going, we all like a good meal. At the end of a long day, or year, or whathaveyou, food (along with kinship) can soothe us in a way that’s hard to describe. Hatchets can be temporarily buried, arguments laid to rest, over dinner. Feuding siblings can be silenced (at least for the moment) with a delicious soup, or a couples’ fight curtailed by the promise of homemade chicken Parmesan. It’s worth a try, at least.

If you’d like to have kids some day, how do you think you’ll go about teaching them to be happy, adventurous eaters?

If I am ever to acquire (not produce) children – which is a big ‘maybe’ in the grand scheme of things – I think I’d stick to my mother’s favorite philosophy: “you don’t have to like it, you just have to try it.” I think this opened a lot of my friends’ eyes to what it meant to be an adventurous eater when we were growing up.

So many parents were primed to say, “you have to eat everything on your plate,” and here was an adult who offered an unfamiliar food with no strings attached. My mother was giving us the agency to not like whatever we were being given, and not have to eat it if it wasn’t to our taste. And it really worked. I can’t think what my life would be like had I not had my first Brussels’s sprout, bite of poached egg, toasted cheese (aka Welsh Rarebit) sandwich, spoonful of black bean soup, or fried zucchini blossom. I certainly would have been the poorer for it.